RUÍNA Arquitetura aims for greater socio-environmental awareness and the appreciation of materials while advocating for reuse as an alternative within the construction industry. In their practice, they explore new avenues for reclaimed materials, diminishing demolition waste and supplying construction materials with a reduced environmental footprint. In 2024, they were selected as part of ArchDaily’s 2024 Best New Practice for their unique attention to context, aiming to minimize its impact on the built environment through the effective reuse of materials and construction waste. Their participation in the 2023 Sharjah Architecture Triennale exemplifies how local ideas can achieve global recognition.

Julia Peres and Victoria Braga, founders of RUÍNA, engage in design exercises and experimental projects in classrooms and on construction sites. They prioritize a circular process that minimizes demolition waste to reduce construction costs. Their approach involves developing strategies for reusing materials, either by restoring them to their original function or repurposing them for new uses. We sat down with them to gain insight into how they view architectural practice through this perspective.

Victor Delaqua (ArchDaily): How do you perceive demolition waste within the context of "the future of construction materials"?

Julia Peres and Victoria Braga (RUÍNA): In contemporary architecture practice, demolition is a predominant theme. Even the act of construction itself often involves a model based on the deconstruction of a place: the intensive exploitation of various natural resources through predatory extraction processes; the underutilization of materials and structures—most buildings and their materials are used for considerably less time than their actual lifespan; and finally, ecologically irresponsible disposal, as if the millions of tons of waste generated daily would simply vanish at some point, which we know will not happen. This linear production system has proven to be fundamentally flawed, and harmful, and now poses a significant threat to the planet's survival.

Therefore, it seems crucial for architecture to regard demolition as an activity of urgent relevance, one that prompts the mobilization of new ideas and proposals attuned to the current era and the most pressing demands of our ecosystems.

The hallmark feature of the urban landscape is undoubtedly the dominance of spaces constructed by human society—primarily shaped by Western cosmology. In this specific environment, demolition and architecture are inseparable, as it is an action without which architecture could not even exist as a practice.

From an awareness perspective, there is a compelling and necessary concept that cities comprise what is often termed "urban mines": they provide all the material resources needed for their own continual renewal, without architecture having to resort to the linear model of natural resource extraction.

Within this logic, which promotes the circularity of production systems, the so-called "resources" would already be available within the city itself, within this "urban mine," on a daily basis.

In this context, RUÍNA regards demolition waste as a valuable asset for innovating new material technologies. We believe that leveraging this waste presents unprecedented opportunities for advancing circular production methods and inspiring more engaging creative strategies, all while upholding social responsibility and contributing to the planet's sustainability goals.

Can you elaborate further on the cost implications, the time required for experimentation, and the prototyping process involving demolition materials during a project until you arrive at the definition of the most suitable technical and aesthetic solutions?

The reuse of demolition waste in a project immediately reduces expenses related to 1) materials (the reduction varies depending on the type of application of these waste materials and the quantities involved) and 2) waste disposal management (primarily rental costs for dumpsters). However, the reuse process may require certain demands on-site, such as storage space for materials and, occasionally, the use of specific equipment to optimize processes—which incurs additional costs.

Reuse is common in large projects, primarily driven by economic considerations rather than ecological ones, owing to the substantial quantities of materials, labor, and access to the machinery involved. However, small and medium-sized projects typically involve minimal or no reuse, despite being major contributors to demolition and civil construction waste (CDW) in urban areas. A lack of information and engagement regarding material reuse in smaller projects often results in stigma due to perceived aesthetic shortcomings or assumptions of substantially lower costs compared to conventional projects. Ultimately, each project's context dictates its approach, with no predetermined rules. However, it is evident that significant cost savings are achievable under favorable conditions, and a range of aesthetic approaches can be pursued to achieve the desired results.

Experimentation and prototyping are essential for discovering the best solutions and understanding the practical limits of reuse. While some processes can be planned and executed before construction begins, others cannot. This implies that the project does not conclude with the design phase. Rather, it remains open to adjustments, modifications, and even new solutions during execution. It's crucial to move away from a linear and rigid procedural approach and adopt a circular movement that fosters autonomy. In this dynamic, whether on larger or smaller scales, the project timeline intertwines with the construction timeline and vice versa.

Reuse materials carry a sustainable appeal and, being unique, deviate from the market logic of mass-producing identical products. Aside from situations where uniqueness is desired, how can these productions or techniques be expanded to a larger audience?

One of the major contradictions of recycling lies in its scalability within the global industry. Transporting recyclable material thousands of kilometers away from where it will be reprocessed to become reusable products often follows a logic not very different from conventional production processes, with outcomes we're already familiar with.

Taking a close look at the concept of locality without forsaking the ability to operate within a network is a necessary and viable alternative path.

Reusing demolition materials on site exemplifies operating at the smallest local scale—the material remains where it was found and is reintegrated into its original or distinct function (as demonstrated in the Paraiso Apartment renovation project). Consider the transformative potential if every small or medium-scale renovation prioritized reusing materials and demolition waste.

In Brazil, recycling and reuse in architecture are still in their early stages in every aspect. Currently, there are no regulations within the construction industry that effectively address these issues. However, initiatives like Arquivo SSA, operating in Salvador, Bahia, stand as pioneering references in this field, engaging in dismantling and reintegrating components for reuse in architectural projects. The establishment of a Public Policy Guide for the Reemployment of Architectural Elements is a crucial step toward allowing these isolated yet impactful practices to expand nationally and become integrated into a broader framework of practice.

Regarding disseminating reflections, practices, knowledge, and techniques, academia plays a crucial role in society. However, we must not overlook a critical perspective, as academia has historically perpetuated classism, racism, and sexism.

As an institutionalized space for the production of scientific knowledge, academia holds significant influence, albeit sometimes belatedly acknowledged by power structures. Therefore, education stands as the most effective tool, with universities being the most strategic spaces for disseminating these practices to a broader audience. This is because such knowledge can be assimilated and integrated into public policies.

This year, RUÍNA has bridged the gap between practice and academia by offering a course at FAU Mackenzie titled "(De)construct and Occupy: Eeuse as a Social and Purposeful Practice", in collaboration with university members, students, and the Ocupação 9 July/MSTC. The methodology and outcomes of the processes explored in the course were documented in a booklet showcasing experiments with construction elements derived from the reuse and recycling of materials.

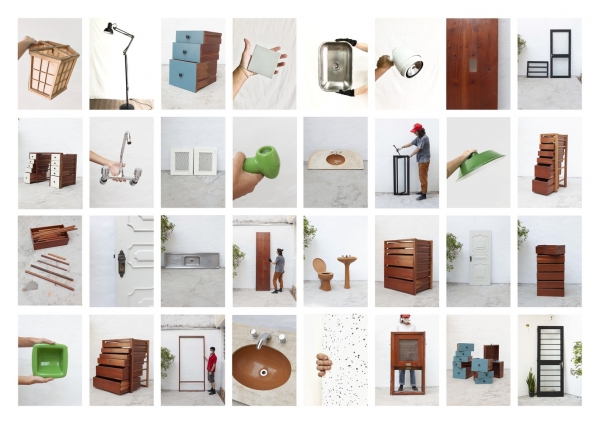

Last year, you launched a catalog of construction materials recovered from demolitions. How do you evaluate the outcome of this project today?

The catalogs we produce are part of a research and action initiative within our firm known as RUÍNA Materials. This initiative is dedicated to identifying and cataloging architectural elements resulting from demolition or dismantling, as well as managing their reintegration into our projects, those of third parties, or even directly with users.

We evaluate the outcome of the catalogs as a dissemination tool and the practice of reintegration as highly positive. It has facilitated engagement with a network of architects who work on construction sites and encounter a significant amount of material that is conventionally discarded daily. This has raised awareness that alternatives exist and are within our reach. Some architecture firms and independent architects who sought materials cataloged by RUÍNA Materials have even adopted this alternative approach to the design process (reversal of the design order), where selected construction elements are considered for use, and the design is adapted to accommodate them.

You also approach reuse as a social and purposeful practice. How do recycling issues cut across these layers?

Architecture, as an applied social science, operates within the realm of inhabited spaces, fostering sociability among both human and non-human entities. Thus, understanding reuse and recycling as integral perspectives and practices within architecture requires acknowledging their inherent social aspect.

Just as in Brazil, a significant portion of the Global South, often labeled as “underdeveloped,” grapples with a reality where reuse is not merely an option but a vital response to underlying socioeconomic constraints. The challenges affecting our nation and many others stem directly from global-scale development, rather than being symptoms of alleged underdevelopment. Hence, the potential for transcending this context lies in advocating for profound shifts in our understanding of development. The envisioned destination seizes upon this insight to champion novel material technologies, fostering autonomy across all socioeconomic landscapes, particularly in areas lacking access to information and means of production. This underscores that raw materials exist and should no longer rely on the planet's natural resource extraction. In architecture, it is crucial to recognize that our knowledge originates from ruins: they shape our perceptions and constitute our most significant epistemological assets. Embracing the concept of ruin, reusing becomes a tool for reclaiming both material and immaterial memory—guiding us to think and act in the present, while acknowledging the past, ultimately ensuring self-awareness and paving the way for a sustainable future.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

▪ Source: Archdaily|https://www.archdaily.com/1017022/reversing-design-order-through-material-recycling-an-interview-with-ruina-architecturel

▪ Words: Victor Delaqua

▪ Photography Credit: © RUÍNA Arquitetura, © Lauro Rocha